How to Build a Food Rescue Ladder

Collaboration is the way.

Food rescue (sourcing surplus food and getting it to people in need) has especially captured my heart these past few months, and it’s a textbook ladder problem. What the heck is a ladder problem, you might ask? Well, I made it up, kinda. But I think it’s a useful framework for thinking about food rescue, and maybe other problems too.

Imagine a hospital has a bunch of leftover food at the end of a day. If they wanted to donate it, there are a handful of barriers they might face:

- fundamentally, hospital employees need to be aware of donation as an option…

- they need sufficient awareness of liability & food safety…

- they need to know about, or be able to find a non-profit that wants what they have…

- they need containers to package the food…

- they need temporary storage if it’s after hours…

- they need transportation to move the food…

- OR be able to coordinate a pick up…

- they need paperwork to track the donation…

- etc. etc.

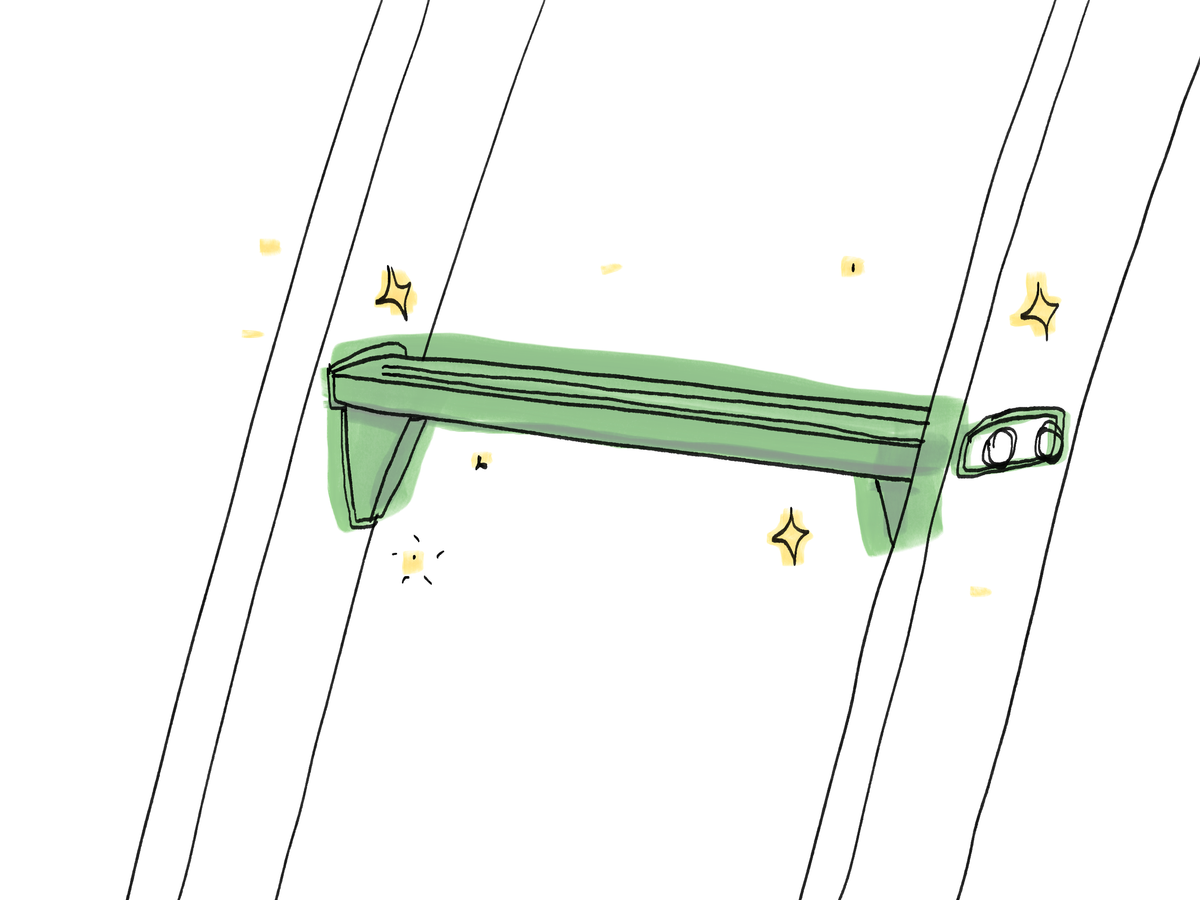

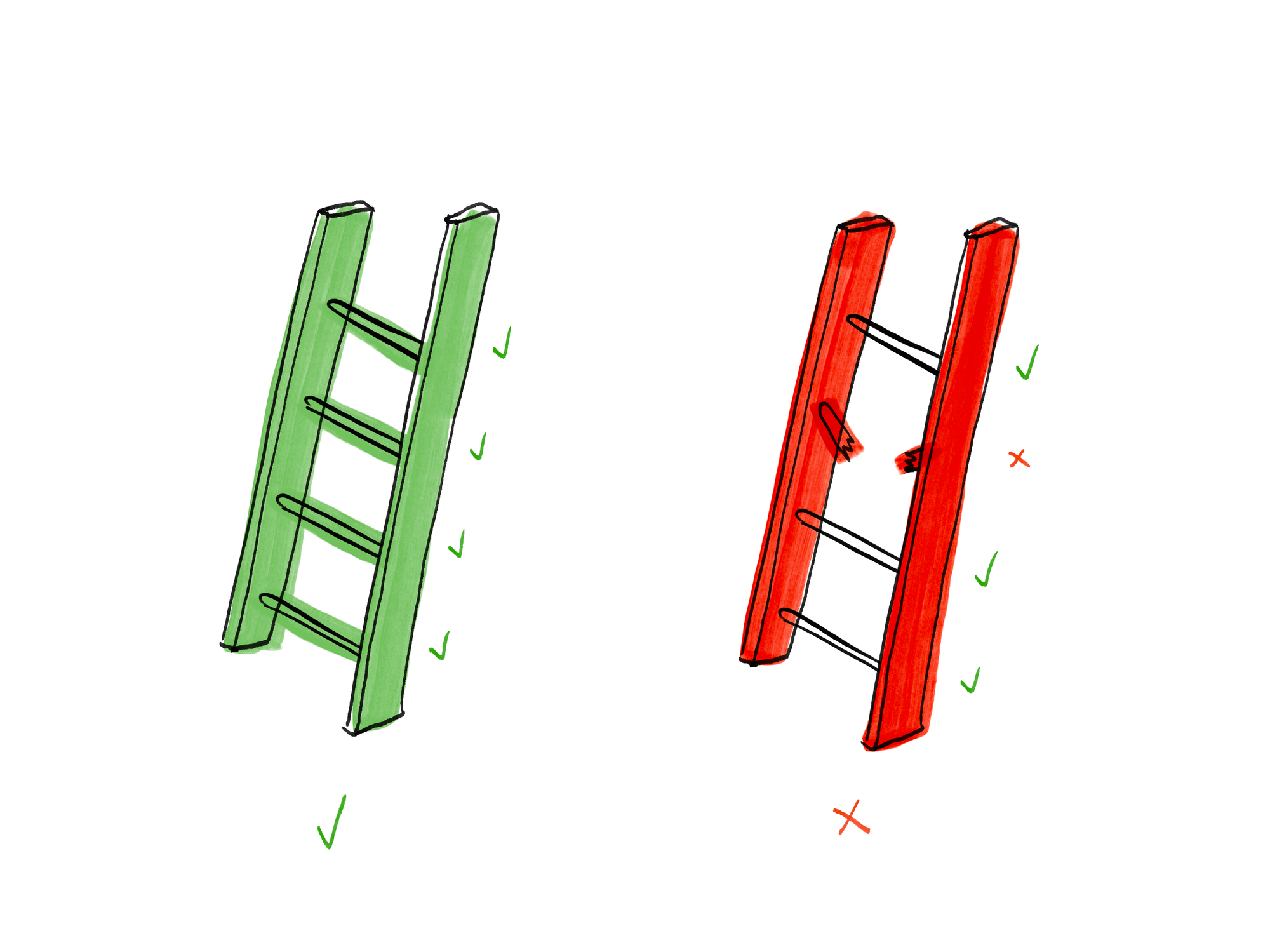

The thing about a sequence of steps like this is that even if one is too hard, the food gets thrown out. In other words, if there's a rung missing, you can't climb the ladder. It’s a ladder problem!

What makes this kind of problem especially difficult is that there are lots of groups implicated in the various rungs (foodservice, non-profits, governments), but they aren’t necessarily coordinating around producing an entire, functioning ladder.

In their article on Collective Impact (which I’m learning is a classic in some circles), John Kania and Mark Kramer critique the social sector for functioning under what they call isolated impact. Funders tend to support promising individual organizations in hopes that they will eventually grow their way toward solving the social problem. That’s the hope–but what normally results is a collection of duplicative, sometimes competing efforts that fail to create systemwide change. The inherent inefficiency of working in isolation may even inflate the perceived cost of fixing social issues. Unfinished ladders abound.

Collective Impact offers a different approach. It's a model for organizing a coordinated effort to change the way entire systems work. You kinda get the gist from the name, but it’s actually defined by specific formal elements:

- Common Agenda

- Shared Measurement Systems

- Mutually Reinforcing Activities

- Continuous Communication

- Backbone Support Organizations

In the years since the original article was published, the promise of Collective Impact has seemingly captured the hearts and minds of social change-seekers. Yet, practitioners acknowledge how challenging it can be to pull off. Examples of Collective Impact are impressive but few, “not because it is impossible,” Kania and Kramer say, “but because it is so rarely attempted."

Beyond the daunting task of getting a large group of stakeholders in a room together, there is a structural reason for this: non-profits compete for scarce, philanthropic resources. They are forced to highlight their individual, isolated impact just to secure funding and continue to exist. This dynamic can obscure collaborative possibilities.

To be honest, I'm still learning about what Collective Impact is and isn't, but I’ve started noticing examples of programs adopting a 'backbone' mindset to tackle problems in the spirit of this framework.

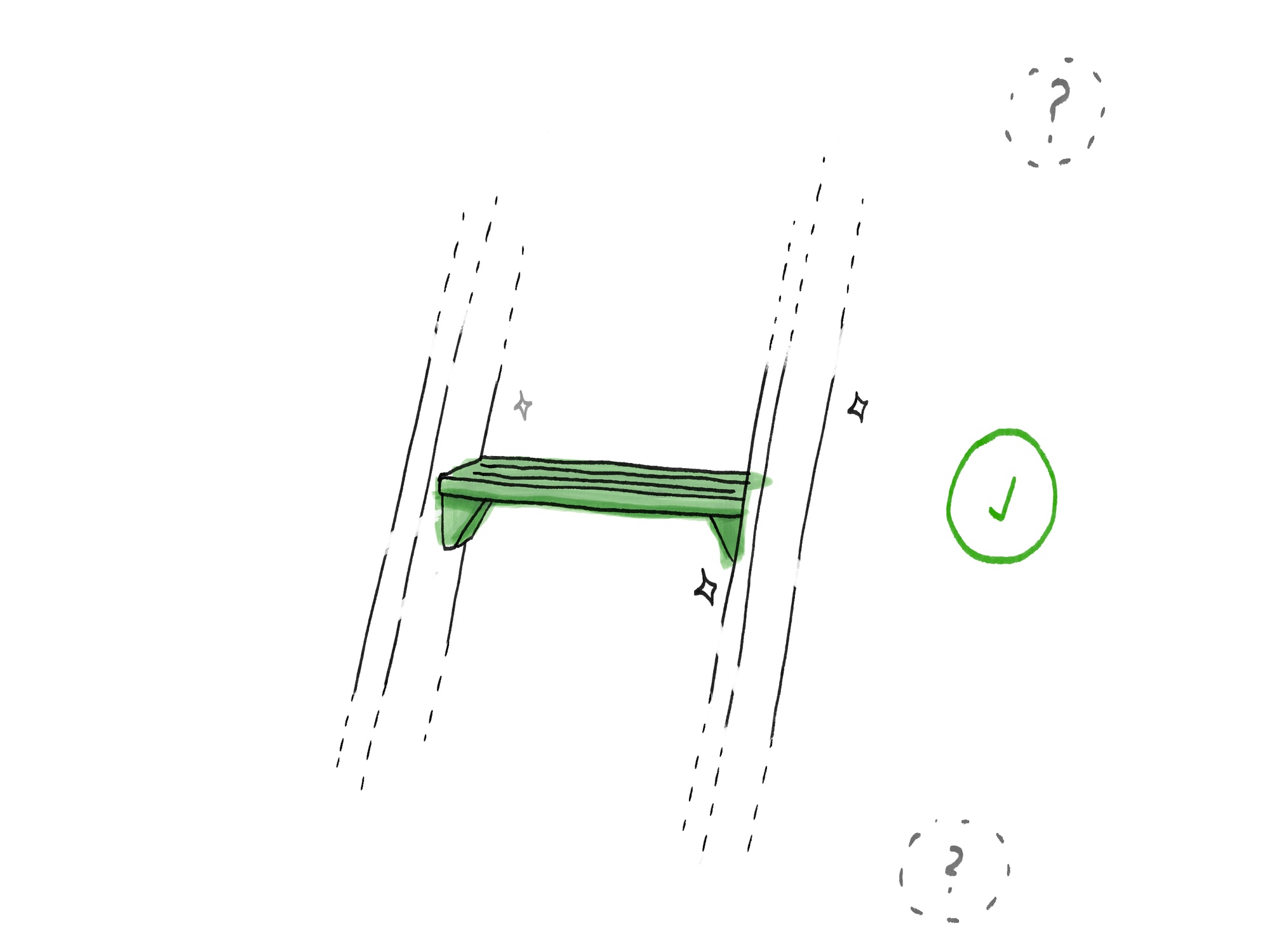

The San Diego Food System Alliance ran a collaborative food rescue program in 2020 with help from the San Diego Food Bank. They provided matchmaking, systems, procedures, and transportation equipment to 15 institutional donors and 4 non-profit recipients who all committed to the effort.

Two years later, participants had saved 50,000 pounds of food and reduced waste by 36%. Chefs who had been hesitant at the start regretted not starting a donation program sooner. This was only possible because the SDFSA took on the challenge of coordinating it.

Efforts like these demonstrate the importance of this approach. Isolation is built into our current system, but if we can carve out small, concrete spaces to work together, we can build ladders that are easy to climb–and prove the system works better that way.