Surfacing Sources of Surplus (Food)

Remixing data and maps

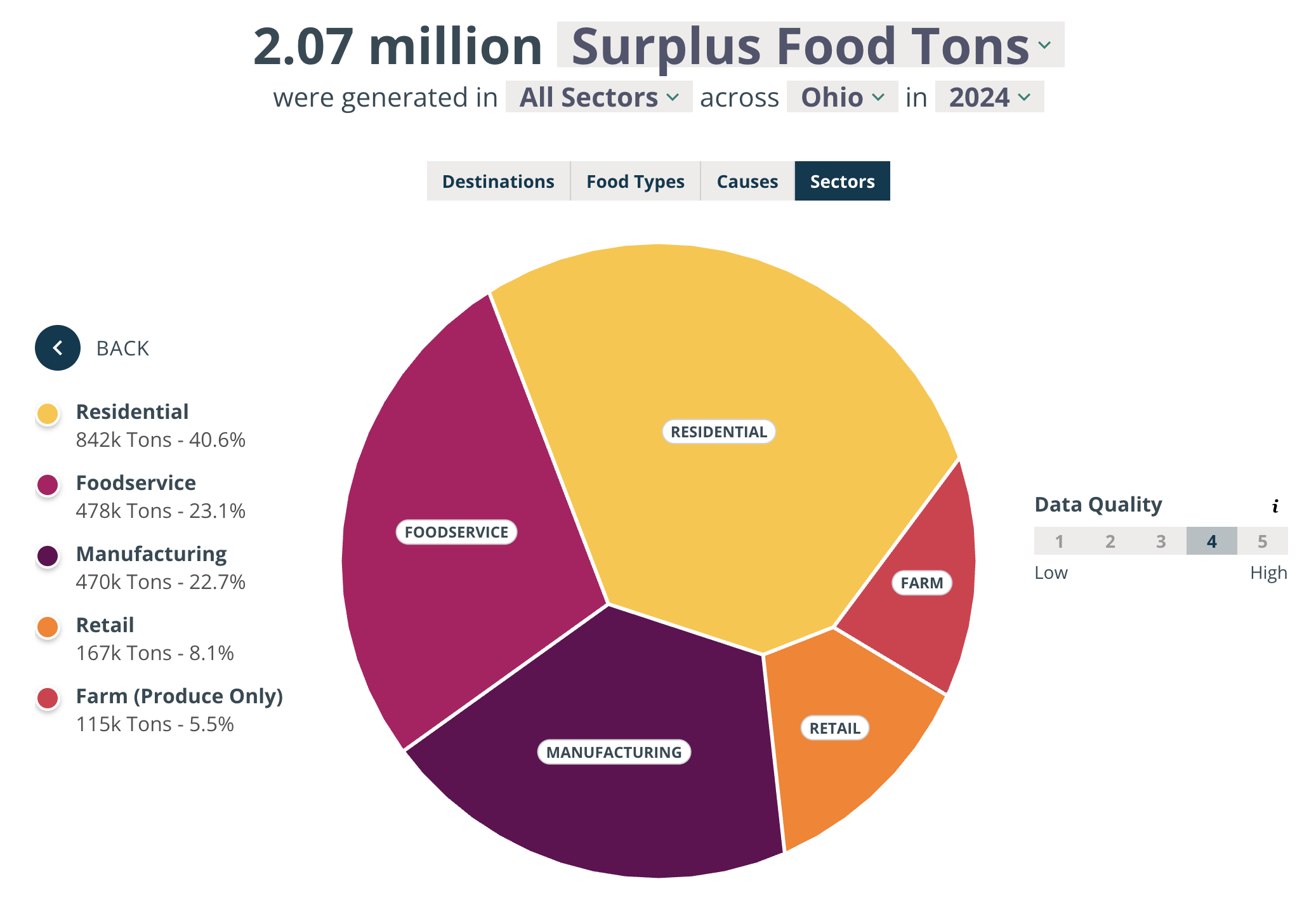

One of the first questions I had about food waste was how we know where the waste is. I mean, we know there's waste:

...but how do we find it? How do we get it? Near me, the Dayton Foodbank has partnerships with heavy hitters like Kroger, while Miami Valley Meals rescues from GFS and a network of small and medium foodservice operations across town. Logic tells you that there must be places with huge surpluses that aren’t yet donating and would benefit from the tax write-offs and good vibes. If you wanted to find those places and help them along in their food waste journey, where would you start?

To learn about the mechanics of this, my attention turned to California. Over the last decade, they've been rolling out a comprehensive waste reduction effort. Starting in 2024, food waste generators of a certain size are required to donate their surplus instead of composting it or throwing it away.

What's interesting about a mandatory food recovery law like this, is that it makes everybody figure out how to do food rescue! Food rescue is super hard–and now, because of this law, California knows how to do it. A lot of the lessons learned are around reporting and compliance, but there are still a lot of nuggets surfacing that are relevant to anyone working on food waste.

For one, the state breaks donors into two tiers, sorted by size and the kinds of logistics they require:

- Tier 1: Grocery stores and big distributors.

- Tier 2: Large hospitality and institutional hubs (Restaurants with >250 seats, Hotels with >200 rooms, Health facilities with >100 beds, etc.).

This got me thinking...if California municipalities are enforcing this, they must have a list of all these generators. Hey...that's what I was wondering about at the beginning!

So how do you make a master list?

Well...there's a PDF that tells you how, obviously. It's actually a bit of work– combining licensing and permitting datasets, NAICS business listings, filtering for things like square footage and seating capacity. The level of precision the California guidance assumes you need is, again, due to compliance requirements–and is probably overkill for finding surplus opportunities in cities like Dayton. We could probably do something much simpler and still identify excess food opportunities...

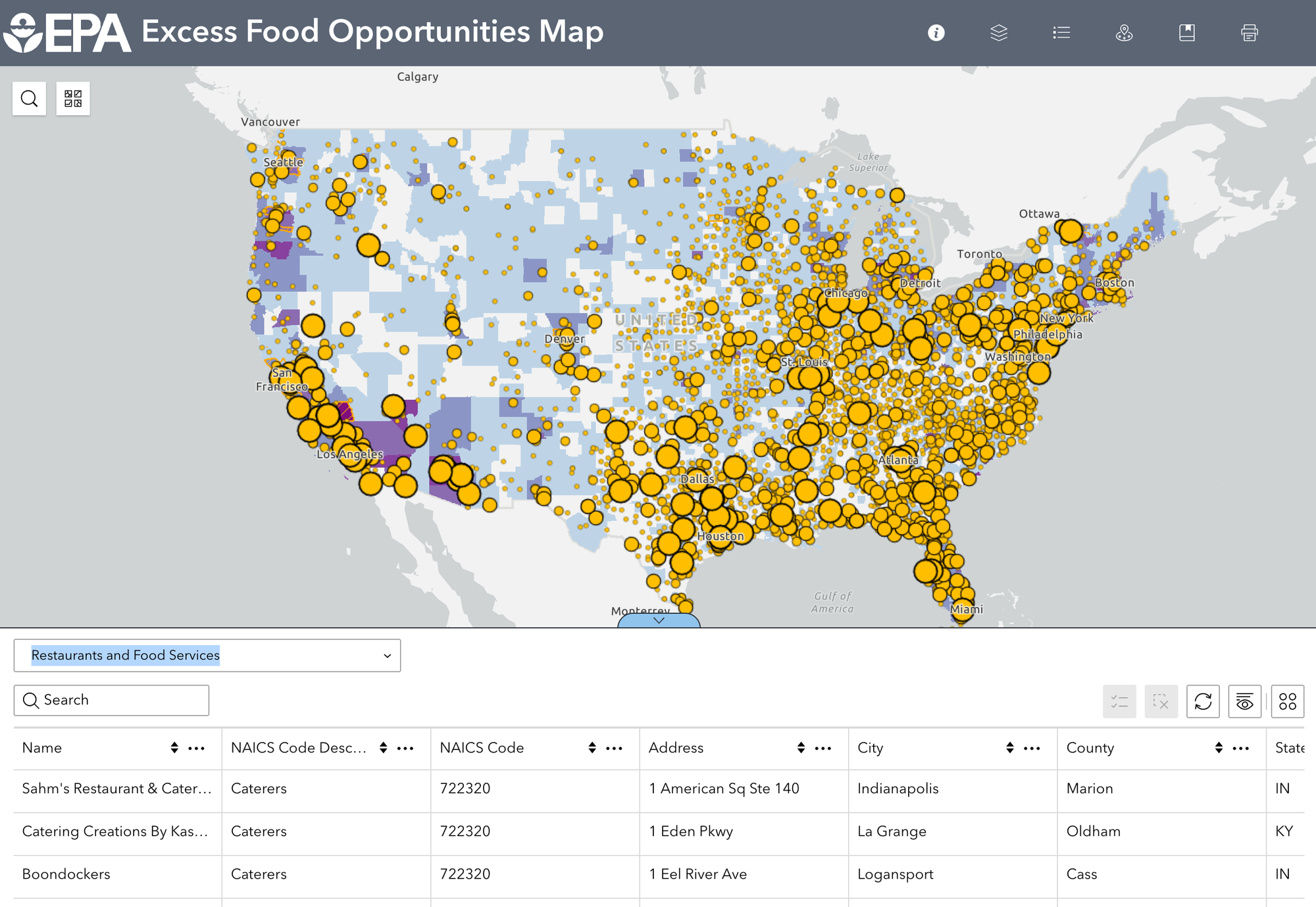

Annnd wouldn't you know it, the EPA already made a thing! A few years ago, they launched an Excess Food Opportunities Map, a tool that uses some fancy math and data triangulation to estimate waste generation across the entire U.S.–basically, a less specific version of California master lists. It's neat! Thank you, EPA!

If you spend some time clicking around though, you’ll realize that this tool is meant to be generally useful to as many people as possible. Makes sense. It's your tax money at work, after all. If you wanted this to integrate into the workflows of the Foodbanks and the Miami Valley Meals-es of the world though, you might make a few tweaks. Since most of the underlying data is public, I decided to build a simplified remix of it with food rescue operations in mind.

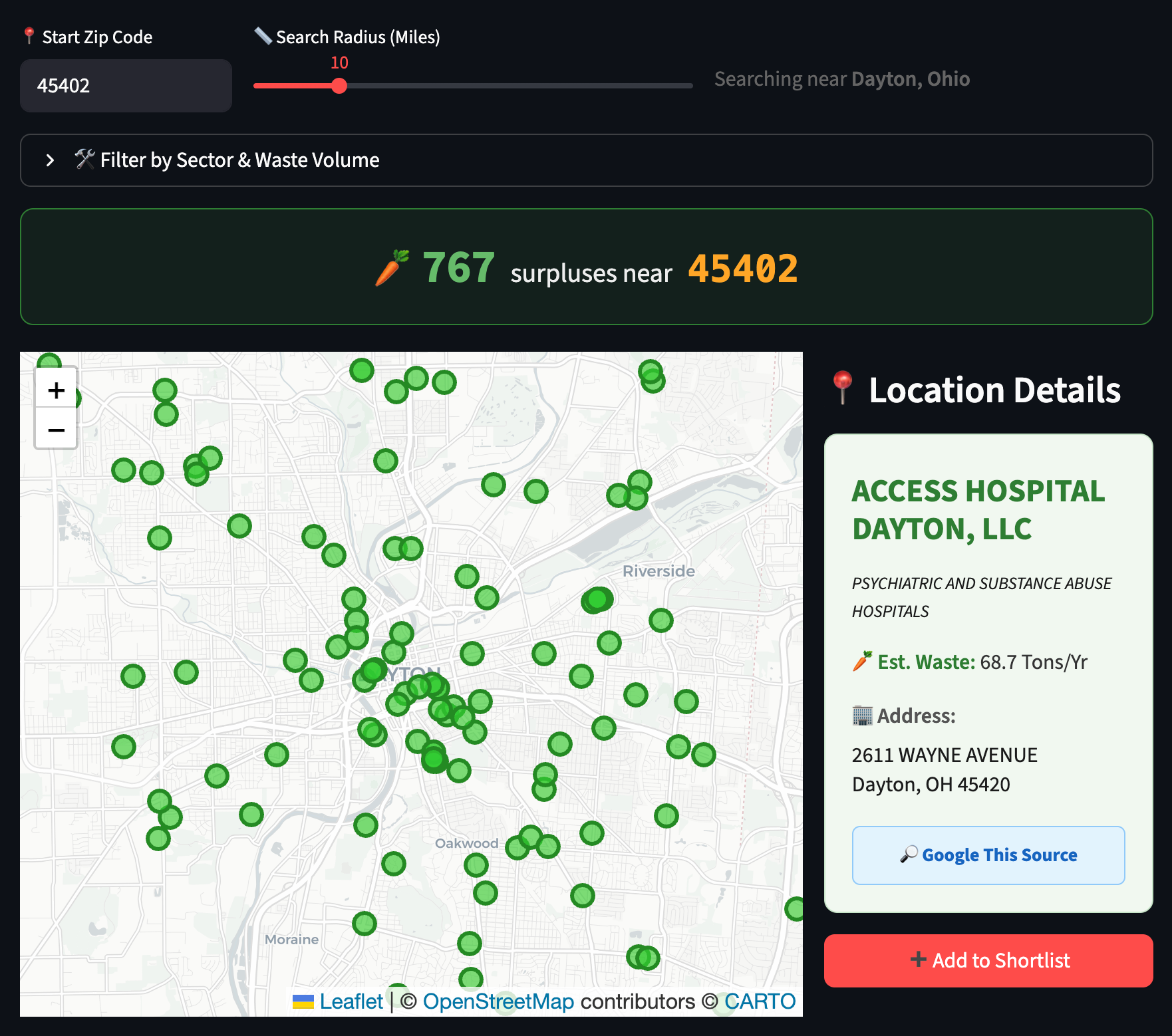

Surplus Food Scout is what I'm calling this little prototype. It lets you enter a zip code, browse a subset of the EPA data most relevant to food rescue, and create a shortlist of leads to export as a .csv or .pdf. The goal is to make it easy to scout and surface some sources of surplus that might be otherwise hiding around town, and make it easy to follow up with them.

As I explored in an earlier post, San Diego successfully rescued 50,000 pounds of surplus food through a collaborative pilot program a few years back. A crucial early step for them was making lots of cold calls to recruit donors. My hope is that a tool like this could make that specific step a tiny bit less daunting.

This is just a first draft, but I'd be curious if anyone finds it useful or has ideas on how to make it better. The EPA site specifically requests feedback on their tool, and it would be amazing to pass along some battle-tested feature ideas to them.

Ultimately, I feel like I got a pretty cool answer to how we know where the waste is. I'm curious now about all the ways we can put that data to use. I'm especially curious about the power of custom tools to visualize and manipulate data in service of very small groups of users. Little experiments like Food Rescue Scout are getting easier and easier to build, lowering the bar for how small a user base can to be to justify building custom software for them. I’m excited to see what's possible when we design tools with these kinds of hyper-specific use cases in mind.